The following is an excerpt from an unpublished manuscript written in the 1990s, the beginning of a second book on the SoHum community. It presents some of the material that appears in Beyond Counterculture: the Community of Mateel, and will provide a starting point for those who have not read that book. As of 2024, the book of which this manuscript is a part remains unpublished, but much of this information was published in 2022 in several chapters of my autobiography, Drag Me Out Like a Lady: An Activist’s Journey, Gegensatz Press, available from Google Play.

https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=QN2IEAAAQBAJ&p

Sure, Why Not? Excerpt from Unpublished Manuscript

Just past the middle of the 20th century, Western society developed a huge crack. Thousands, maybe millions, of newly formed and forming citizens fell into it. Some experts called this event “the generation gap” and saw it as the inevitable result of dropping the Big Bomb at the end of World War II. Others blamed the later advent of television or the allegedly “permissive” childrearing methods promoted by Dr. Benjamin Spock. Most people called it a collapse in morals and blamed the fallen themselves—an ungrateful bunch who simply had been spoiled rotten by Spock followers or post-war abundance or both.

The occupants of the crack themselves, however, experienced it as betrayal. They were, or had been, the most American of Americans. Their problem was not ingratitude or immorality. Their problem was that the American values they had been taught actually rendered them unsuitable to survive in the reality that America was becoming. The greater their allegiance to the loftiest ideals of America, the less competitive they were in the corporate workplace. American to the marrow of their bones, they had believed that every little boy could become president if he tried hard enough. (Rare were the little girls or children in shades of brown who consciously questioned the inequal premise of this belief. After all, who had ever seen a female president or one whose skin was dark?)

They had believed that, in the words of the Sunday school song, “red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in His sight.” They had believed that Americans were the good guys who saved Europe from the bad guys in the last war, as seen in the war movies, and that Americans would always be the good guys. They had loved John F. Kennedy and many had actually joined the Peace Corps or wanted to. Their problem was that they had failed to grasp that they were only expected to give lip service to the ideals of equality, self-reliance, personal freedom and personal merit. No one really expected them to sacrifice anything for those ideals and, indeed, doing so was a quick path to tribulation.

They were born into a time when, for all but a handful, mindless conformity was becoming the only way to survive industrial civilization. It was as if the world were collectively holding its creative breath, lest any change precipitate still another unspeakable horror—perhaps this time a nuclear war to end all life on Earth. The prophet of this social stagnation was Joseph McCarthy, who was most active when the more precocious of the early and pre-baby boomers were just starting to read newspapers. The vehemence and comprehensiveness of his attacks on freethinkers and suspected freethinkers, working from the very core of a government ostensibly founded on the notion of liberty, was a paradox that became increasingly obvious. Though the influence of the committee in which he was so prominent, the House Unamerican Activities Committee, began to lose its obvious influence long before the counterculture got started, and it did exist until 1975, its longterm effects were felt well into the childhoods and adolescences of the future dropouts.

Many of these were preset to question the conformist paradigm by some particular condition that made it difficult for them to fit into the homogenized ideal family depicted on TV or in their schoolbooks. Maybe they were too fat, too thin, too poor, too disabled, too gay (to use today’s word). Maybe they were girls too smart to be “a real woman” who could catch “a good man,” or boys too sensitive or poetic or thoughtful or musical or artistic to meet the exacting standards of fifties masculinity. They may have formed controversial political opinions, such as being in favor of integration in the South. Whatever their secret difference, many knew early on that there was some lie behind the golden picture. The emotional impact of the assasination of John F. Kennedy was, for many, a most dramatic validation of that suspicion, nevermind the political explanations for that event that were established much later.

During the mid to late 1960s, demonstrations against racial inequality became demonstrations against the Vietnam War, as the draft claimed more and more young men, particularly those without the financial or political means to escape it. Those who had bought the American values of tolerance and equality now felt betrayed by the refusal of parents and teachers to even admit that anything at all unusual was happening in America. Discontents were dismissed out-of-hand as examples of normal adolescent rebellion, in spite of the unprecedented nature of the historical situation and the fact that neither the Civil Rights Movement nor the anti-war movement were by any means the exclusive purview of the young.

Universities and other duly constituted authorities scrambled to restrain students from their escalating efforts to expose the lie that all was well. That those authorities did not leap to assist the young in their defense of the highest American ideals was experienced as the profoundest betrayal, the ultimate in rank hypocrisy. Instead of being hailed as the courageous and honest idealists that they were, students and other young activists were expelled, arrested, evicted, ridiculed, fired, divorced and disinherited.

When marijuana and psychedelics were added to the mix, at home and among soldiers in Vietnam, the break was complete. If the catchphrase “this does not compute” had then been in use it would have become “and furthermore, it’s absurd.” What meaning remained for them at all, whatever shreds of personality had survived tear gas, riot guns, attack dogs, combat and the monolithic hypocrisy of formerly respected elders, was now dissolved or reworked by the deep cleaning power of LSD and marijuana. Some died here. Some were permanently damaged, by anyone’s standard. Others wandered in limbo for hours, days, years, sorting through the shards of their exploded lives looking for something that worked. Some found it.

Especially for those who had believed most in America, who had fought in the streets for justice only after all else failed, the message of the psychedelic was—forget it. Discussions took place everywhere as to whether it was productive to “become a Nazi in order to fight the Nazis.” The graffiti “off the pig” became “off the pig in you.” Better to abandon the old way, stop trying to beat them at their own game. It’s too big and they own it. Your game is inside your head. You can rearrange that freely, choose what to toss, what to keep, what to nurture.

The Cold Duck Commune and Band sets out from Minneapolis in an old school bus, headed for Canada in 1969. Among them, Vietnam vets and others who had been at the Chicago protests against the war. The bus broke down in Miranda and that is where they settled. Photo probably by Rick Klein, provided courtesy of Lloyd Hauskins.

The revolutionary Weathermen went underground politically and began engaging in tactics consciously rejected by those who became the counterculture; the newly forming counterculture went underground spiritually. There was a bumpersticker that said, “What if they gave a war and nobody came?” A bumpersticker for the counterculture could have been “What if they gave a society, and nobody came?” That’s what “dropping out” was. Children of affluence and poverty alike saw that working for the war-machine, even if the war-machine would employ you, meant losing all hope for meaning or integrity in your life. For the draftees, working for the war machine could well mean losing your life, period.

Sometime in the mid-sixties, it all reached a breaking point: fighting the war, stopping the war, being gassed and shot at, being stonewalled by people you were supposed to worship as your professional superiors, their reaction when simple questions were asked. For thousands of people at the same time, the whole social structure of America came crashing down at once. Careers, marriages, futures, inheritances and all predictability disappeared. It was painful, but it left a more or less clean site to build on.

Members of the Cold Duck Commune on the road. Photo probably by Lenny Anderson, provided courtesy of Lloyd Hauskins.

Having bid farewell to their futures, they saw no point in staying put. Cities had become unbearable to people made keenly conscious of their environments by psychedelics. Bob Dylan asked bitterly, “You ask why I don’t live, here. Honey, how come you don’t move?” Former political activists and, mostly younger, apolitical runaways did move. They hit the road and kept on trucking. They became known collectively as “hippies.”

There were nomadic hippies and sedentary hippies, communal and individual hippies, religious and secular hippies. Some ended up going back to what they had left, maybe with new insight, maybe with a lifelong hatred of hippies. Some became “acid casualties,” never having managed to reconstruct their minds after deconstructing them with LSD. Others were drawn or tricked into more lethal drugs. Some ended up in drug-free ashrams following gurus, perhaps as mindlessly as the LSD had made them, perhaps not. Some formed communes or intentional communities of which some, perhaps, still exist.

Where They Went

This book is about the ones that settled in northern California, 200 miles north of San Francisco, near the town of Garberville. They are a particular instance of that part of the countercultural movement that came to be known as “back-to-the-landers” or the “voluntary simplicity” movement. What makes them unique in the back-to-the-land movement is that, rather than living in isolation on parcels of land interspersed within a mainstream community, the back-to-the-landers in southern Humboldt and northern Mendocino counties were able to settle whole watersheds previously undeveloped. The rapid concentration of great numbers of people who shared overpowering experiences resulted in their creating a community of their own from scratch. This community not only resulted from the spirit and flavor of the sixties, but inevitably made the sixties viewpoint its foundation. The community had values and goals, in spite of itself. One of the values was to not have goals, but that was a sophistry soon made moot by the rapidity with which social connections were formed to meet social needs unmet otherwise, such as appropriate schools and medical organizations. The community, for a time, was a vast laboratory where social experiments were “kitchen testing” possible routes of change for the wider culture, whether the wider culture wanted it or not, whether the testers themselves realized it or not.

The geographical area in which there may be found people who subscribe to the ideals of the back-to-the-land movement covers northern coastal California, much of Oregon and who knows how much of the West in general. There are, or have been, in addition, many similar communities all over the United States. The community described here, however, very probably had, at one time, the densest concentration of sixties idealists of any population in the world. There was, in other words, a higher ratio of self-identified countercultural individuals to mainstream individuals in that area than could be found anywhere in the world.

Dancers at a hippie-organized crafts fair in Benbow CA, 1970s

This high concentration of similarly oriented people produced the most cohesive non-intentional community of sixties dropouts there was and perhaps still is. The historical waters were greatly muddied, starting in the 1980s, by the growth of the marijuana industry and the cross fertilization between sixties dropouts and local mainstream residents, so that whether the community as I described it in my book “Beyond Counterculture” still exists or not leads one into a great semantic bog. What community? Who’s a member? Where is it?

Muddy waters notwithstanding, a picture of the community as it once existed is still informative to students of culture change. How did it fail, if there is a sense in which it could be said to have failed, and why did it last as long as it did are still relevant questions to anyone hoping to make culture change a tool in addressing the near hopelessness of the current picture of the human species and, indeed, the biosphere.

Much controversy has centered around what words to use in talking about this community and the mainstream community that predates it. The word “Mateel” was coined about 1980 to refer to both a geographical area and those residents within it who subscribed to the values outlined by Deerhawk, the poet who coined the word. Mateel combines the names of the two major watersheds in the general area occupied by the countercultural community, the Mattole and the Eel. I used it in the past to describe a geographical area that included those watersheds, and certain others, and the cultural system generated by the countercultural residents of that area.

I have used the adjective “Mateelian” in the past but have since tended to not use it. This is a word coined in my previous work for discussion purposes only and was never used by Mateelians themselves. The word “Mateel,” insofar as it was ever used by Mateelians, came into question early on and then increasingly because the one organization that permanently incorporated the word into its name, the Mateel Community Center, kept it only after an agonizing showdown between those who took the purist position that it was a local organization formed for locals and those who wished to vastly expand the scope of the organization and seek funding from non-local sources. Though the name was ultimately retained, the organization has appeared to many to have strayed from the original values that word hoped to describe.

For those reasons, I will use the word “SoHum” here to refer to the same geographical area I described in Beyond Counterculture. This is a commonly used shortening of the phrase “southern Humboldt County,” but everyone who uses it understands that it includes parts of northern Mendocino County as well. I will refer to the countercultural residents of SoHum as SoHummers and to non-countercultural residents of SoHum as the local mainstream population.

I do this with the caveat that the two communities, once easily identified by their values, are now not so easily identified. I will leave it to others to decide whether it is still accurate to speak of a SoHum or a Mateel community separate from the now somewhat merged community that has been created by the interaction of SoHummers with mainstream residents and the non-countercultural emigres who came later, drawn directly or indirectly by the marijuana industry.

Mutually perjorative terms are “redneck” and “hippie,” but more tolerant individuals from either side recognize these words as loaded and use them accordingly. They will usually refer to themselves that way ironically, or to the other group by the pejorative, only among themselves. Some people, including second-generation SoHummers will joke that they are both–hipnecks– and the intermingling of the two groups in agribusiness partnerships, employment situations and Romeo-and-Juliet marriages makes this joke closer to reality than outsiders might realize. Complicating the picture is what I have called in the past the “we-are-not-here” syndrome, the reluctance of hippies in general to accept any kind of label, suspecting that labels themselves are a source of misunderstanding.

In most areas of contemporary America these days, the word “hippie” has significance only in a historical context. Any reference to a contemporary reality must be preceeded by a qualifier that indicates the writer or speaker’s own youth or modernity, such as “aging hippies,” “freeze-dried hippies,” “unreconstructed hippies,” all of which have appeared in the media, including “hip” media founded by hippies.

The existence of some kind of unusual social situation near Garberville is well-known to the California public, indeed, the international public. The media has extensively covered the marijuana industry, which it often portrays as centering there, though what few statistics have ever been produced to support that assertion are open to question. The press has mentioned the community as well in the course of covering the “timber wars” between environmentalists, largely countercultural, and the timber industry. Because of these journalistic biases, SoHummers are viewed by the public as being hopelessly behind the times, clinging to long-debunked sixties values and/or caught in some kind of Twilight Zone time warp that makes them irrelevant to current affairs.

Hippies on retreat, 1970s.

This view is based on the assumption that the hippies of Humboldt somehow froze time and never went beyond their sixties incarnation to something new. This, in spite of the many concrete successes achieved by local environmental and civil rights groups and the fact that, at least in the past, SoHum lived and breathed social change and progress. Had it not been so, the word “beyond” would not have appeared in the title of my former work.

If you call someone a “hippie” in SoHum you are using a word that is vigorously alive in the language. Whether it will be received as a compliment, an insult, a joke or a simple statement of fact will depend entirely on the motivation of the speaker and the self-identification of the receiver. Pretending the word is passe is, for the most part, another sophistry. SoHummers may disagree on the value of their tenure as hippies or the validity of those values, but only a handful would seriously deny that hippies or their values never existed. Even their enemies, with some notable exceptions, will admit that hip values were at one time alive and well and, what is much more important, were being manifested.

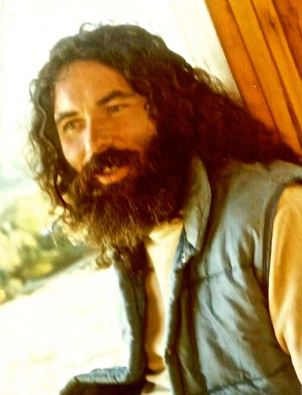

One of the earliest founders of the SoHum community, Larry Bliss, unreconstructed hippie to the end.

Many whose hippie credentials were pure in the early seventies now actively seek to deny that there ever were two distinct cultural communities and to erase any lingering obvious differences. Others adopt the attitude “hippie and proud of it.” The latter group sees the former group as a bunch of opportunistic cop-outs, especially since the more outspoken members of this group are often running for public office, opening new businesses in town and/or joining local mainstream organizations such as the Garberville/Redway Chamber of Commerce or stand to profit in some other way by sacrificing the original values in lip-service to tolerance. The former see the latter as “separatists,” who draw unnecessary lines between people and thereby perpetuate hostility between the two groups.

The SoHum community was born out of the conflict of the sixties and founded by people who made the choice to go to SoHum based on their individual experience of that critical time. Today it also consists of two major secondary groups. One was drawn to the community after it became large enough to support them. The other came, irrespective of values, solely to grow marijuana.

The first group includes professionals who generally are sympathetic with sixties ideals, but prioritized their careers over the rewards of dropping out. They are, to varying degrees, analagous to what political activists in Berkeley in the 60s used to call “teacup liberals,” a phrase coined by University of California anthropology professor, Gerald Berreman. They could only come when the community of dropouts was large enough to support them. They largely include health professionals and attorneys, two groups welcomed with open arms by hippies tired of the intolerant treatment they often received from local mainstream health professionals and attorneys.

The second group includes organized criminals, tenant farmers and legal or illegal immigrant workers, all drawn to the area after news of the marijuana industry spread. As a group, they are distinguished by economic, rather than spiritual motives. Though it is possible that many that came only to grow marijuana subsequently were influenced by their countercultural neighbors, it appears more likely that their influence on SoHum was greater. With them came robberies, murders, guns, fast cars on dirt roads, fires started by ignorance and carelessness and the reintroduction of a “me first” attitude, in contrast to the semi-communal worldview of the original hippies. In response to these factors, many is the peace-loving hippie grower who reversed his or her position on guns.

There are also parents, children and siblings who came to SoHum to be close to their hippie relatives when it became clear that their relatives were here to stay. The flow of dropouts of all ages continues. It came to include more persons from foreign countries than originally, though not any more persons of color,* a criticism that has been leveled at SoHum by its various observers. It has also included new arrivals in their twenties who are often indistinguishable in appearance from the dropouts of the 60s and 70s. They arrive in Keseyesque vans and old schoolbuses, wearing granny dresses, buckskin and fringe, offering beads, candles, pipes and crystals for sale on the street and looking pretty much like the hippies of yore.

Where they are coming from

The history of SoHummers begins where the history of SoHum and the general counter-culture intersect. It started when and where it did because certain SoHum ranchers discovered there was a category of buyers who actually needed land that anyone else would deem worthless. The economy of SoHum, having boomed and busted its way through a series of industries, hit another slump with the exhausting of the timber resource. The population was declining; unemployment, rising. The only resource left was the logged over land itself, but any fool could see it was unsellable. It was steep and brushy, full of poison oak. Water sources and building sites were erratically distributed and there were few access roads and no electricity or phones.

Logged over hillside typical of much land owned by hippies

Meanwhile, thousands of dropouts were driving around the country in old vans, pickups and buses looking for somewhere to settle. Mainstream SoHum residents needed a new source of income and dropouts needed a cheap place to live. It took more than complementary needs, however, to start a symbiosis as unlikely as this one. It took a lucky, some might say cosmic, connection. This connection was made by rancher Bob McKee.

McKee is a near-mythological figure in the history of SoHum, in that hundreds of people who never had direct dealings with him know that he is the father of the counterculture in SoHum. The descendant of a family of oldtime SoHum ranchers, he became a real estate agent in the mid-sixties, at a time when real estate was not a hot item there. His contribution was to take the dreams of the dropouts seriously and take a chance on their ability to make the change from urban to rural living, given their abyssmal lack of knowledge of what this change entailed.

Once the word got around on the hippie grapevine that McKee had broken his ranch into parcels and was selling them cheap, dropouts began to arrive. They came in communes, individually and in families nuclear and, by their own definition, extended. They came in old schoolbuses, caravans of pickup trucks with campers and on foot, hitchhiking. Those first years, they lived in tents, tepees, abandoned tool sheds, tree houses and the chicken house they built first, after kicking the chickens out when it started raining.

The yurt/trailer combo or shed/tent/trailer combo was a common early home arrangement.

Interior of an owner built one room tiny cabin.

They lived in their vehicles, funky old trailers, abandoned sheds and barns and long-deserted bunkhouses. They lived under large pieces of plastic stretched over pole frames. In the early 70s, the number of “homesteaders” reached a kind of critical mass and they began to organize themselves beyond the family or commune. A community began to emerge from what had appeared to be a very large refugee camp.

Encampment at a retreat attended by about 300 hippies in the late 1970s.

Stories of “how I got to SoHum” often resemble each other, even now. Nonconformists, in families, communes or individually, are traveling around the country looking for a place to live inconspicuously, peacefully and productively. They find SoHum most often by visiting friends already there or because someone they trust to understand what they are looking for told them about it, often someone they picked up hitchhiking or who gave them a ride.

This is, of course, a perfectly rational and predictable way for a community of likeminded people to form itself. There is, however, a surprisingly large number of people whose story has a cosmic element, an opportunity that appeared for them just as they arrived in SoHum, an event that insisted that they stay, a dream or vision that could not be denied or ignored. An enormous number of people simply stumbled into the community while wandering around and knew they were home.

One couple, for instance, had left the unsympathetic atmosphere of Texas with their three children and headed off into the unknown to find a place where their unusual history would not dog them. The man had been a middle-aged priest/philosophy professor at a Catholic college, whether celibate or not, he would never tell me, when he fell in love with his freshman student, who asked him pointed and unanswerable questions after class. Their affair resulted in the loss of his job and vocation and the birth of their three children. Several years of living with the moral disapproval of their Texas neighbors decided them to seek a more sympathetic climate.

After months of traveling, camping out, living in their car, they followed the suggestion of a hitchhiker they picked up in Arizona and headed for northern California. Their car broke down in Miranda. By the time it was fixed, they knew they were home.

Another SoHummer had just been released from San Quentin after six years. In a daze and completely at loose ends, knowing only that he really didn’t want to go back to jail, he was picked up hitchhiking by a carload of hippies. He ended up living with them in Marin County. By the time they decided to check out SoHum, he was well on the road to rehabilitation as a hippie and went along with them, to live a happy and productive life in the land of the redwoods.

Daryl Cherney, one of those led to SoHum through a random contact.

Daryl Cherney, the well-known folksinging environmentalist, famously tells the story that he had left New York and was hitchhiking cross-country when he was picked up by a Native American spiritual leader who did not live in SoHum, but was a frequent visitor. After hearing Cherney’s views on the spiritual importance of the environment, he suggested SoHum, then proceeded to drive him there and drop him off at the Garberville office of the Environmental Protection Information Office. It was there that he would find his vision, and he did, according to my subsequent interview with him.

What they think they are doing

The counterculture got its name from social historian Theodore Roszak, who observed, accurately, that sixties dropouts were doing more than simply withdrawing. They were actively trying to change industrial civilization, what Roszak called “the technocracy,” by seriously altering the way they lived their everyday lives. To the extent that anyone had a goal, that goal was to reverse, or counter, the effects of the technocracy, aka The System, the military-industrial complex, the war machine, the corporate state.

As these appellations suggest, the bottom line in dropping out was always economic. Sacrificing one’s earning potential was the most drastic action to be taken, short of suicide. The extent to which one had taken this action was also the litmus test applied by the counterculture to anyone claiming dropout status. It was the countercultural equivalent of putting your money where your mouth is.

Roszak’s observation and the word he coined to describe it was and is “right on” for outside observers and inside intellectuals (“intellectual hippie,” strange to say, is not necessarily an oxymoron, at least in SoHum.) However, the vast majority of SoHummers I interviewed and observed have vehemently denied they were countering anything.

They have said, with the greatest of truth, that they were looking for personal freedom. Personal experience being the paramount source of knowledge leading to the dropout and informing the post dropout period, they often used to deny conscious political motives and said they simply wanted to live as freely as possible. It was only when critical mass had been reached, when enough peope seeking personal freedom arrived in one spot, that they began to consciously work on finding a better way to meet needs that had formerly been met by the state.

Dropping out was a highly individual action. You did it when the time was ripe for you and to the extent that you were able. Making a new society, on the other hand, was something best done with a little help from one’s friends. The universal problem was how to survive after you’ve quit your straight job, dropped out of school, turned down the graduate fellowship, refused the inheritance or run away from parental or spousal support and whatever strings might have been attached to it. The counterculture approached this problem in several ways.

Lowering the overhead was the first approach, reversing status markers so that poverty was more respected than wealth. Sociologists referred to this procedure, often snidely, as becoming “downwardly mobile” or joining the “nouveau poor.” To the extent that this experiment was shortlived for the children of the middle class, the snideness is perhaps justified. However, there were many on whom the new image “took,” at least as an ideal. At the very least, the spectacle of a large portion of the upcoming generation saying “no thank you” to their anticipated share of the nation’s riches served to throw the connection between money, status, power and exploitation into clear relief.

One overhead-lowering strategy was the commune. Housing is cheap if it’s four to a bed. Rice costs less if you pool your money or food stamps and buy it by the 50-pound sack. Transportation is cheaper if it’s six to a car rather than one or two. Better yet, stay home with twenty of your closest friends, call it family night and party down. When communes began to disappear, the communal strategy lived on in the form of food cooperatives, “food groups” wherein people not otherwise economically connected bought food together in bulk to save money.

Other ways of lowering the overhead included scavenging, bartering both goods and services and stealing from large corporations or the state. Opinions varied widely on the righteousness of this latter method and a lack of clarity on the concept was responsible for many bad vibes. One suspects that the prevelance of the concept “right livlihood” emerged as a reaction to this strategy. Right livlihood is however one can survive economically without ripping off someone else or contributing to a part of the mainstream system that rips off someone else.

The significance of communalism in SoHum, however, does not lie in the continuing existence of communes, but in the continuing existence of the social bonds formed by fellow communards and the retention of the values and skills learned during the communal experience. There are at least two reasons why the communes themselves generally did not survive the move to SoHum. The first is what social scientists might call structural. It has to do with the conflict between existentialist freedom on the one hand and the communal diminution of the individual on the other.

The first Mateelians consisted of those countercultural individuals who found it hardest to submit to any formal authority, including that of a rigid or hierarchical commune. The uniqueness of the Mateelian community stems largely from the fact that its members are such rugged individualists. The community is not only nonintentional, but, because of this emphasis on individualism, it was, perhaps, even inadvertant. It resulted, like a spontaneous combustion fire, from the failure of collective energy to dissipate, not from any great master plan.

Evidence of this is that the communes formed by those who later became Mateelians were almost universally chaotic, egalitarian and tolerant of nonconformity. Former communards in SoHum can seldom even specify what exactly was communal about their commune. Implementing the communal ideal is not at all that easy in a capitalist context, no matter what kind of commune it is. Maintaining a commune composed of people who value personal freedom over almost everything else is well-nigh impossible.

The Cold Duck Commune bus landed in Miranda, on a ranch owned by a local family, who rented them the old bunkhouse. They remained a commune there for years, then members went on to separate land partnerships. Here, the bus has been sitting on the ranch for many years, a monument to the roots of the SoHum countercultural community.

The structural reason for the demise of communes in SoHum is that, ironically, once they became established in SoHum, the all-American individualistic ideal with which they had been raised, even though it may not have been practised around them, reasserted itself. The individualism of the communards had been redefined to include environmental, egalitarian and cooperative values but, in the long run, only a commune with a narrow, overriding goal and some rationale for discipline, like religion, can survive the materialistic, competitive climate of America.

The second, psychological, reason for the decline of the communes is that, as the counter-cultural community became increasingly visible, it began to supplant the commune as a source of emotional and moral support. Early communes offerred emotional sanctuary for the new dropouts, who were often under severe attack from non-dropouts. That kind of emotional support is not so necessary in SoHum, as it is in places where hippies are in the minority. The countercultural ambiance was at one time so pervasive in SoHum that the need for “courage in numbers” was greatly reduced.

Good friends comfort each other after a funeral.

Over the years, as many casual observers have noted, the original values of right livlihood, voluntary simplicity, communally oriented social strategies, alternative ways of meeting social needs and even environmentalism, have been merged and submerged with the predominant mainstream values. Although many of the earliest hippie-founded organizations still exist and their founders can still point to their achievements in the face of impossible odds with great pride, many are the former SoHummers who abandoned the community, unable to bear the disappointment of seeing it fall so short of its original promise.

Many are the current residents of SoHum who came only to grow marijuana, brought hard crime with them and were never motivated by anything but greed in no way distinguishable from the greed of corporate America. Many are the original hippies who traded their alleged values for money the very instant marijuana growing made that possible. Many are the mainstream locals who did not hesitate to invest in or indirectly benefit from SoHum’s latest boom industry while either recasting themselves as hippies to learn the biz or while denouncing hippies and keeping their own biz a secret. The ethnographic study I conducted between 1971 and 1985 could not now be done for these reasons. The current book is an effort to reconstruct the spirit and flavor of those days from interviews with the participants, done in the early 1990s, when that time could still be remembered with joy.

View of Bear Butte from Elk Ridge. Photo by Jerry Pruce.

*This statement was still true when I wrote in the 1990s. However, as I post this essay in 2018, I feel obliged to say that there are now visible in SoHum many more persons of color than there were in the 1990s, as well as persons speaking languages other than English. Without statistics, I cannot assess the degree to which complaints I heard from persons of color in the past about feeling isolated are still reflected in the numbers, i.e. the ratio of white residents to persons of color. I can only report my observation that I see many more black people in town than I used to.